Global Food Security Under Threat?

- bayestimes

- May 14, 2022

- 5 min read

Author: Maximilian Debatin

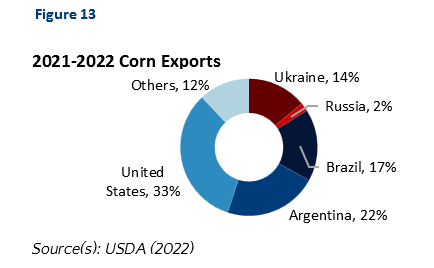

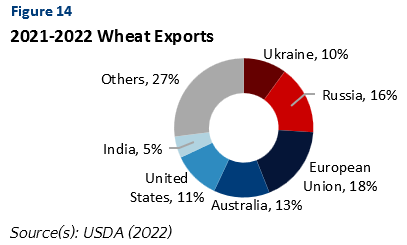

The Russian attack on Ukraine raised concerns about global food security. As Figure 13 and Figure 14 show, Ukraine and Russia account for 16% and 26% of global corn and wheat exports, respectively. Thus, they are immensely important exporters of agricultural staples and play a crucial role in the intricate global food system. With seaports in the Black Sea shutting down due to the war, fears of losing Ukraine and Russia as agricultural exporters arise. This would have dire consequences for food security and would be felt especially by weaker economies, like conflict-torn Yemen. The World Food Program expects the Russian-Ukrainian military conflict to lead to increasing food prices in Yemen[1].

The root causes of the looming food crisis reach further than the war in Ukraine, however. Svein Tore Holsether, CEO of Yara International, one of the world’s major fertilizer producers, already warned at the COP26 conference last fall: “I’m afraid we’re going to have a food crisis”. A number of factors, such as climate change, exploding energy prices and supply chain squeezes have been adding to the perfect storm for the global food system.

This week’s deep dive will take a closer look at the underlying risk factors that threaten to upset food supply and what that would mean for different countries. Finally, the implications for the dry bulk segment are addressed.

CROP YIELDS ALREADY UNDER PRESSURE FROM CLIMATE CHANGE

The agricultural sector was already strained, even before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The effects of climate change are starting to take their toll on harvests[2]. Although rising atmospheric CO2 concentrations stimulate plant growth in theory, rising and increasingly fluctuating temperatures as well as extreme weather events offset that effect in practice[3]. NASA research has shown that corn yields could decrease by 24% until 2030, which would have “severe implications worldwide”[4].

FERTILIZER CRUNCH DETRIMENTAL FOR FARMING EFFICIENCY

Furthermore, the agricultural sector is experiencing an unprecedented fertilizer crunch. Russia is not only one of the world’s largest exporters of grains (wheat in particular), but also a major producer of low-cost fertilizer. Sanctions on Russian fertilizer as a consequence of the war would be felt by farmers around the world. The significance of Russia’s role in the global fertilizer supply is underlined by calls from Brazil's Agriculture Minister Tereza Cristina Dias to exclude fertilizer from sanctions imposed on Russia. Brazil relies on Russia for 9m tonnes of fertilizer, accounting for 20% of its fertilizer imports in 2021[5].

As Figure 17 illustrates, fertilizer prices have almost tripled since spring 2020, in tandem with exploding energy and particularly natural gas prices. Fertilizer producer Yara International announced its decision to curtal its European ammonia and urea production to 45% of nominal capacity, citing that natural gas prices have become too expensive for economical fertilizer production[6]. Svein Tore Holsether pointed out that the cost of producing ammonia fertilizer has increased almost tenfold within a year, from $110/tonne in summer 2020 to $1,000 in 2021[7].

The soaring prices and scarcity of fertilizer mean that farmers have to face increasing harvest risks and will not be able to farm their land as efficiently as previously. According to fertilizer producer Nitrogenmuvek, the absence of certain fertilizers could reduce crop yields by 50%, underlining the importance of an abundant fertilizer supply for food security[8]. Mr. Holsether from Yara International argues that while the fertilizer shortage will be felt by consumers all over the world, it can mean the difference between life and death for those in developing countries[9]. Even if farmers manage to procure fertilizers for their crops, they might not be able to fuel their tractors and machines. With crude prices reaching record highs, the diesel to fuel tractors and other agricultural equipment becomes prohibitively expensive.

CHINA’S STOCKPILING EXACERBATES THE CRISIS Meanwhile, the decaying global food security situation is further exacerbated by China’s stockpiling of grains such as corn, wheat and rice. According to the US Department of Agriculture, the country is projected to hold 69% of global corn reserves, 51% of global wheat reserves and 60% of global rice reserves by mid-2022[10]. These inventories are enough to feed the Chinese population for one and a half years. At the same time, worldwide stockpiles have fallen for five years in a row and stand at 596m tonnes currently. China’s excessive stockpiling comes at the expense of rising agricultural commodity prices and growing food insecurity in other parts of the world.

EXPLODING AGRICULTURAL COMMODITY PRICES

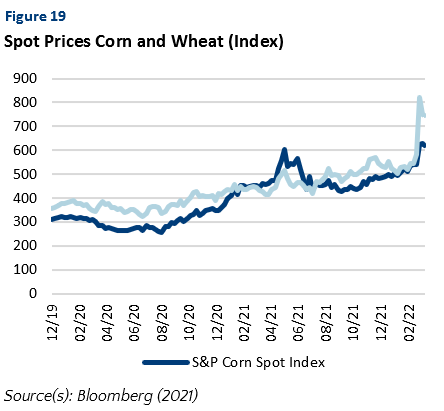

As a result of climate change, the fertilizer crunch, excessive stockpiling and the shocks introduced by the war in Ukraine, food prices have soared in recent months and days. The already high prices are further compounded by inflation, rising labour costs and currency devaluations[11]. Figure 19 shows that corn and wheat prices have approximately doubled since Mar 2020. Prices of wheat spiked in particular as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The UN Food and Agricultural Organization’s food price index was 24.1% higher than a year ago[12].

These price hikes especially impact consumers in low-income countries, as they tend to spend a larger share of their income on food. In a recent update, the World Bank reports that a significant number of consumers in these countries have begun to reduce their food intake or have even run out of food altogether. The number of people facing acute food insecurity has also increased. These developments are reversing the efforts made towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals[13].

WHAT DOES THIS MEAN FOR DRY BULK SHIPPING?

Agribulks (which include grains and fertilizers) are among the three main dry bulk cargoes (along with coal and iron ore), and account for roughly 10% of the total dry bulk volume. Grain trade is highly seasonal, and the vessels used to carry grain vary with the trade (as a general rule of thumb, larger vessels are used for longer hauls). Cargoes from the Black Sea are usually lifted on smaller dry bulkers, such as Handysizes or Supramaxes.

The food crisis sees two effects weighing against each other in the dry bulk market. On one hand, the lost Ukrainian and Russian grain volumes will have to be sourced from elsewhere, leading to an increase tonne-mile demand. This could benefit the larger dry bulk vessels, which lend themselves to longer-haul trades. On the other hand, the fertilizer shortage and the war in Ukraine and Russia will put a significant dent in overall agricultural output. Paired with low global grain inventories, this translates into dwindling seaborne trade volumes and shipping demand. It remains to be seen which one of these two effects will prevail.

[1] Reuters (2022) [2]World Bank (2022) [3] US Environmental Protection Agency (2016) [4] NASA (2021) [5] Reuters (2022) [6] Yara International (2022) [7]Yahoo Finance (2021) [8] Bloomberg (2022) [9] BBC (2022) [10] Nikkei Asia (2022) [11] World bank (2022) [12] Food and Agricultural Organization (2022) [13] World Bank (2022)

Comments